August 05 2019

Rolex has been in business for well over 100 years, and has seen many trends come and go. For the most part, they have left the shortest lived fads for others in the industry. Perhaps the last time they were forced to jump on any prevailing bandwagon was during the quartz crisis, and they did that with a distinct lack of ambition.

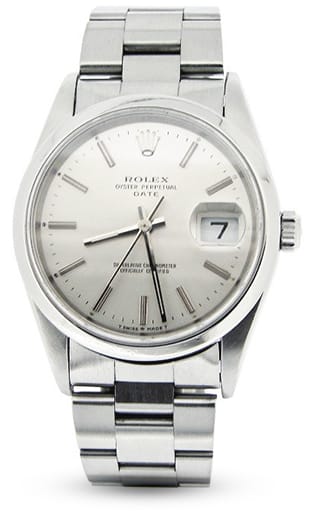

The bulk of their current collection was actually established in the middle of the last century and has remained essentially the same pretty much ever since. A Datejust from 1945, for instance, is ostensibly the same design as the Datejust you can buy today, outwardly at least.

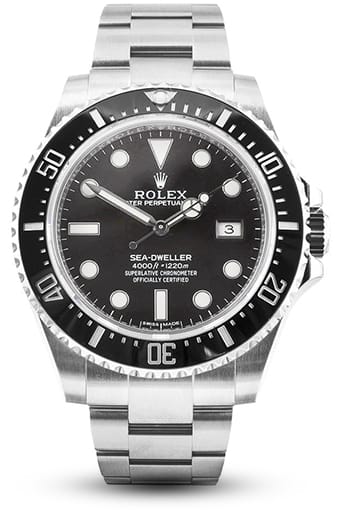

The one concession to keeping up with the crowd Rolex has participated in, and again, only very recently and much later than their contemporaries, is in the question of size. Some of the biggest names in the portfolio have suddenly found themselves ballooning in proportions of late. The Sea-Dweller grew from its time-honored 40mm to 43mm in the latest iteration. Both the DJ and the Day-Date were granted larger versions not long ago, at 41mm and 40mm respectively. The newest releases, such as the Yacht-Master II and the Sky-Dweller, are significantly bulkier than the accepted Rolex standard of old.

The race for ever bigger watches all stemmed from a shift in tastes that started at the end of the eighties and quickly degenerated into a competition between several brands; who could create the most outrageous, over-the-top symbol of conspicuous consumption? Soon, we were getting pieces in the 50mm+ range, with companies like U-Boat going even further and creating great hockey puck-like efforts measuring more than 60mm.

The Far East Market

Rolex, to their credit, stayed away from the worst excesses of the contest entirely. The company has a long history of sticking to its ideals, even in the face of great pressure.

As one example, the truly iconic Professional models in their range; the Submariner, the GMT-Master and the Daytona, have all remained stubbornly at 40mm, even after many years of consumers remarking those dimensions are just too small for a modern tool watch.

Fortunately (or unfortunately, depending on your sensibilities) the battle to create the biggest watch on the planet seems to be over. The 2008 economic collapse forced Swiss watchmakers to turn to the vast, untapped market in China to sell their wares.

There, the overriding taste for sleeker, more elegant designs has caused brands to rein in on the real behemoths and we have started to see a reversal, with many mainstream marques now producing the sort of watches more reminiscent, size-wise, to what they were pre-1980s.

Rolex, for their part, build models across a wide spectrum of measurements, but with the unspoken understanding that anything below 34mm or so is aimed primarily at women.

It hasn’t always been the case though. In the earliest days of the company, wristwatches for men were both rare and far smaller than would be popular today.

Sign of the Times

The turnaround in image of the wristwatch as a male accessory took its first steps in 1910, when Rolex scored the first ever chronometer ranking from the Official Watch Rating Centre in Biennefor for one of their models. This testament to the accuracy of their timekeeping was followed up in 1914 by a class ‘A’ certificate from the U.K.’s Kew Observatory, something only marine chronometers had achieved up until then.

Both of those pieces were powered by movements from Rolex’s longtime compatriots Aegler, who specialized in making the sort of tiny, intricate mechanisms found in ladies models—at that time, the only audience for wristwatches. Pre-WWI, men almost exclusively used pocket watches, with anything else more or less unthinkable.

When the Great War broke out, the practicality of a wearable watch quickly became apparent. Officers were expected to purchase one from their allowance, and Rolex’s burgeoning reputation made the company one of the first ports of call. They, like many others, produced what became known as Trench Watches, a sort of halfway point between the pocket watch and the wristwatch as we know it today.

Many of these were simply small, classically shaped pocket watches, some coming complete with hinged front and back covers, with thick wire lugs soldered on to allow for a strap to be fitted. Even though legibility was of prime concern, and they usually featured large numerals and highly contrasting dials, the size of these pieces rarely exceeded 32mm.

The Art Deco Years

The between war years were dominated by the Art Deco movement. Characterized by bold geometric profiles and highly stylized forms, it influenced just about everything from architecture to fashion, and especially watch design.

At Rolex, it led to a number of avant-garde shapes, perhaps most notably for the era, the Prince.

The striking rectangular shape was pure Gatsby, and the dual dial display, with a running seconds sub counter beneath the hours and minutes dial, led to them being the favored watch of physicians, as it made it easier to time a patient’s pulse. The ‘Doctor’s Watch’, as the Prince became known, was driven by one of the legendary Rebberg movements from Aegler, shaped to have the winding barrel at one end and the balance at the other, leaving enough room in-between for a mainspring long enough to grant a 58-hour power reserve.

Although the setup meant the Prince was a relatively long watch, sometimes stretched as far as 42mm or so, the standard width would be only around the 25mm mark, leaving it looking particularly slim and neat on the wrist.

Enter the Oyster Perpetual

The first of Rolex’s two industry-defining achievements arrived in 1926 when they perfected the waterproof Oyster case. The idea of screwing down the bezel, case back and winding crown against a solid middle section to form an impenetrable shell did more than anything else to completely alter the persona of the wristwatch. No longer too fragile for everyday use, now they could handle anything thrown at them.

The first of the Rolex Oysters, a name that would become synonymous with the great and the good from all walks of life, also followed the Art Deco styling conventions. Softly rounded cushion-shaped designs were most prevalent, along with some sporadic octagonal examples, very few of which, as usual, would measure more than 32mm.

The move towards an increase in size really only started a few years later, in 1933, when Rolex unveiled the second of their groundbreaking innovations.

Their self-winding movement was introduced inside the ref. 1858, the first watch ever to wear the Rolex Oyster Perpetual tag that has remained on nearly every one of their models to this day.

These earliest watches stayed at around the 32mm mark, but required thicker cases with deeply convex backs to accommodate their new, revolutionary calibers, compared to all the manually-winding pieces that had come before. That extra bulk left them christened with the unofficial nickname ‘Bubblebacks’.

The Second World War

What was for so long the archetypal size for a classic Rolex watch wouldn’t arrive until the 1940s.

The Second World War had seen aerial combat come of age, and pilots from Britain’s RAF had taken to replacing their government-issue 30mm Rolex Speedkings with the larger and more readable Oyster Perpetuals out of their own pocket. Hearing of this, founder Hans Wilsdorf set about creating a series of ‘Air’ watches as a dedication to their heroics. With names like the Air-Lion and Air-Tiger you would be forgiven for thinking these would have considerable heft to them, but that pair still only measured around 32mm on average. Even the Air-King and the so-called Air-Giant were just 34mm.

However, in 1945 the first of the perennial Datejust models emerged, weighing in at a conspicuously large 36mm, and became the base line for Rolex’s output for generations.

With only a few exceptions, men’s watches from the brand would stay at 36mm and above from then on. Anything smaller would generally be promoted as a ladies watch, or else a mid-size model, aimed more often than not at a Far East market.

Rolex’s main aim with the dimensions of their output, as well as the aesthetics, has always favored versatility above most other considerations. It is one reason they were never dragged into the great oversize watch race, and their portfolio has long reflected the prevailing styles of the times. Their earliest models drew heavily on Art Deco’s urbane, ultra stylish influences, and the diminutive sizes were a necessary match.

As years have gone on, tastes have changed and been mirrored by ever larger watches.

While we will probably never go full circle and see the majority of men sporting models of sub-32mm as they did in the 1920s, there is a definite return to more manageable sizes, and Rolex’s catalog is stuffed full of some of the best examples money can buy.